Frenchman’s Cap is considered one of Tasmania’s most prominent treks through rainforest, scrub, boulders and cliffs. The mighty white monarch is Tassie’s version of Yosemite’s Half Dome and is found deep in true remote wilderness in the Franklin-Gordon Wild Rivers National Park, surrounded by rainforest, lakes and river.

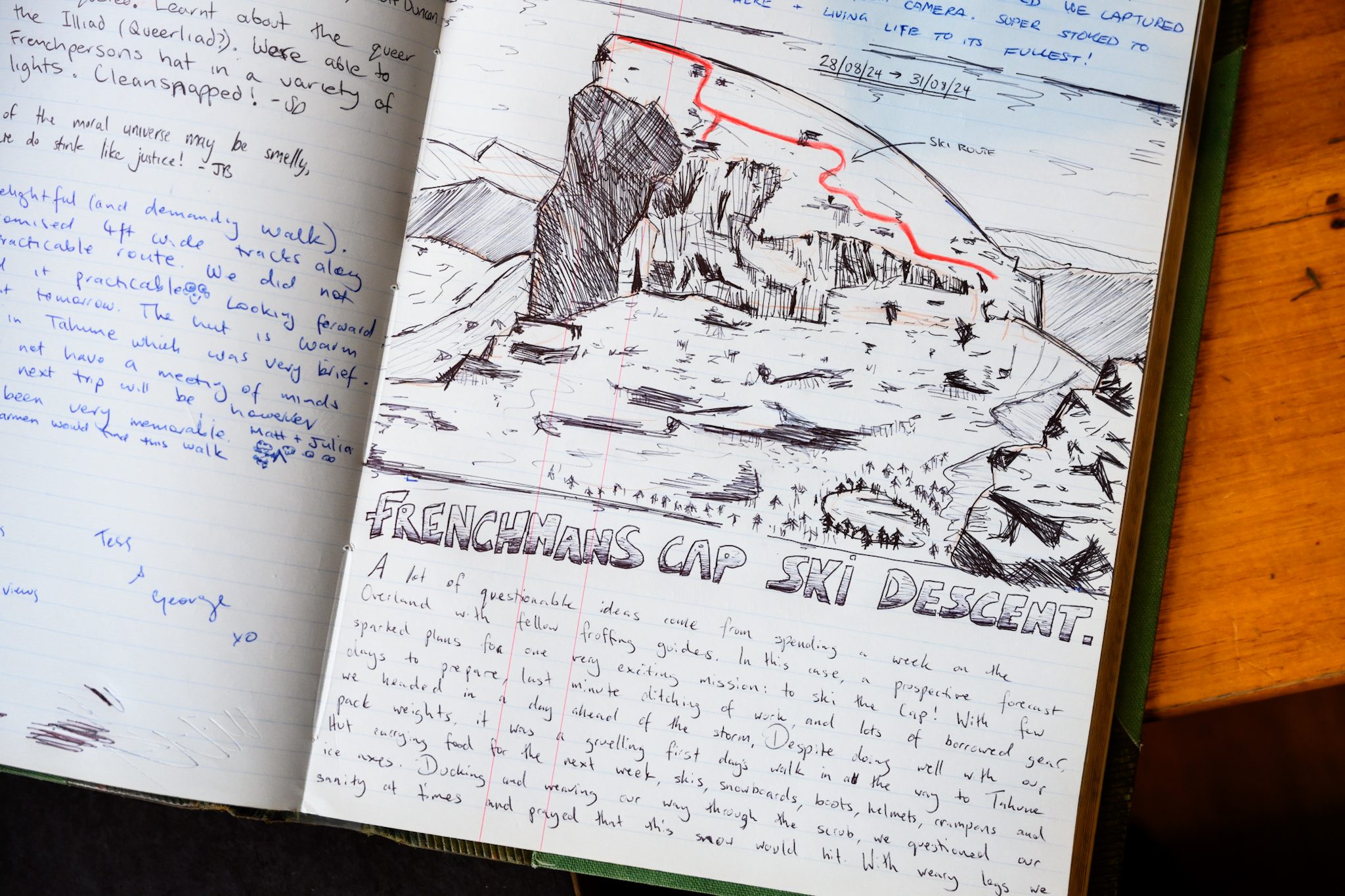

Come winter the 1446m mountain can be covered in treacherous snow, luring only the a handful of daring adventurers to conquer the Cap’s ascent with an equally daring ski descent. Shaun Mittwollen, Hamish Lockett and Sakura Woods tackled the peak in less than stellar conditions this winter just gone, with surprising results.

This is their story as told by The North Face athlete Shaun Mittwollen.

We edged our way higher on the mountain approaching a tilted chasm with an overslung roof. An easy scramble in summer but in the midst of a proper winter blizzard this was a whole other ballgame.

Rime ice coated all available surfaces like a frozen coral reef and wicked spindrift rained down occasionally from above accompanied with unexpected westerlies gusts. On the roof ornate rows of icicles some as large as cave stalactites dripped from the smooth quartzite slabs.

I coughed as I breathed the frigid air, somehow finding myself with covid-like sickness whilst marooned in the Tassie mountains. A calculated choice to make the most of the conditions after several terrible winters in a row. Perhaps the only chance?

Joining me were two friends who were eager to be roped into a winter adventure in the mountains, Hamish and Sakura, who I’d ridden the spectacular Myoko volcano earlier that year.

We were piecing our way up Frenchman’s Cap. One of Tassies classic summits and an impressive late winter storm was impacting our latitude producing snow to a few hundred meters above sea level. Better late than never as they say.

The proud quartzite monolith was rumoured to once hold a semi permanent snowdrift just below the summit that would often last through the summer. Australia’s last glacier?

Seeking miniature cracks under the ice we leverage our way up the awkward slot passing our packs one by one. Reaching the most spectacular part of the climb Hamish’s camera began to suffer with the constant attack of moisture. The shutter began to fire continuously and the camera became unresponsive.

We removed the battery and tried again but the camera was dead (and remained that way until a week after sitting in rice it made a miraculous recovery). Luckily we still had my trusty Nikon Z7 to photograph with but even that was beginning to behave erratically.

- Sakura and Hamish making their way up Frenchman’s Cap. Photo credit: Shaun Mittwollen

- Hamish precariously ascending. Photo: Shaun MIttwollen

- The going gets tough. Photo: Shaun Mittwollen

- Just keep walking. Photo: Shaun Mittwollen

- Skier Shaun Mittwollen on Frenchman’s Cap. Photo: Hamish Lockett

- Sakura Woods on Frenchman’s Cap. Photo: Shaun Mittwollen

Above the awkward slot we were in the cloud and beyond a series of airy rock slabs the terrain mellowed into a collection of small bowls filled with deep windblown snow. We post holed upwards at times up to our waist leaving footprints tinged as blue as a glacial crevasse, such was the depth of the snow. Cutting left we rounded under a band of cliffs towards the humongous south face, a vertical cliff face as large as the mountain is tall.

Here the cliffs dropped precariously into the fog and to my surprise the couloir entombed in the cliffs looked well filled in and very skiable. I’d sighted this couloir once before but it seemed so objectively hazardous to even note into my mental list of ski descents. But today perhaps was the perfect chance.

The snow was dense and forgiving for steep skiing and no cornice overhung the line which teetered down to a flattish bench before plunging into the fog and what would be 200m cliffs. We continued up to the summit but I couldn’t take my mind off the couloir- I’d already vowed to return on our descent.

Topping out the summit was horrendously bleak. A horseshoe pile of rocks marked the high point on an otherwise featureless moonscape scrapped clean by the incessant winds. Meagre protection against the freezing rain and blowing ice that pelted the exposed sides of our faces. Removing gloves to faff with bindings and camera gear was a painful experience indeed and our fingers were numb within ten seconds or so. The windchill must have been close to -20c.

Despite the summit being largely devoid of snow a thin slither had collected on the lee of a small roll. We decided to follow the ribbon cautiously downhill until reaching a large stack of rocks with a gully on one side. Here the snow had filled in much more and with Hamish filming above I decided it would be great to ski this one fast.

A bit of an optimistic decision- my skis nabbed a rock on my second turn and sent me tumbling downhill. It was back to conservative storm skiing from then on.

- Shaun Mittwollen about to drop in on Frenchman’s Cap. Photo: Shaun Mittwollen

- The ski line. Photo supplied.

For Tassie, the snow quality was excellent. A step above the wet heavy snot we are used to and easy to slash without resorting to jump turns. Cutting right under a band of cliffs we found a small drop to session for a few hits before making our way back to the main couloir.

I’d scoped out a nice angle on the ascent and gave my camera to Hamish before cautiously dropping into the chasm. A few cursory jump turns and then traversing wide to a shallow bench above a small cliff line. The chock into the lower bench was all rather concave and rock infused so I elected to return to the col where Hamish and Sakura were patiently waiting in the exposure. From there we weaved down the ascent route retracing our bootpack around bands of cliffs that would surely fill in during a deeper snowfall.

We managed to keep our skis and boards on our feet from the summit all the way to the top of the crux which we had climbed a few hours earlier making a satisfying descent of the main face and a good deal more vertical than my previous attempt in 2021.

During an exceptionally big snow year I’m sure the descent could be extended all the way out to Lake Tahune, doubling our skied vertical. However with climate change wreaking havoc on already fickle snowfalls in Tasmania these occasions are far fewer. Perhaps once or twice a decade. For now we take what we can get.

Once back at the hut in respite of the weather we began to receive reports of the storm worsening. Five days of mixed rain and snowfalls together with 120km/h+ winds and even forecast thunderstorms. It wasn’t unexpected however having achieved our goal of a ski descent of Frenchmans Cap we decided we’d have time for another strike mission to a different mountain if we made it out before fallen trees and flooding blocked our escape.

It was time to exit the mountains as we beat a hasty retreat to the lowlands stoked to finally have the chance for a decent backcountry ski mission after several disappointing winters.

Little did we know. The winter of 2024 would continue to deliver.