It’s that time of year again. The lull between ski seasons, when all the pseudo-armchair-meteorologist theories get trotted out, declaring which part of the world will be thumped with powder this northern hemisphere winter.

Will the west coast of the US go dry after last year’s insanity? Or will the east surprise everyone and smash the snowfall records?

And, while we’re here – why did Australia have such a dismal season just gone? We went to the weather experts to find out.

[El Niño] winter is coming

If you haven’t heard, headline news for 2023-24 is the global shift from a La Niña/neutral weather pattern over the past two years into the infamous El Niño pattern.

Predicting the weather in a few days – let alone many months out – is a tricky thing to get right. However, there are some general trends that meteorologists have identified during El Niño years. Looking back at historical snowfall data during El Niño years can help identify patterns and provide more surety of where the snow will hit hardest.

“There are two reasons we talk about El Niño and La Niña,” says meteorologist and founder of US snow forecasting site Open Snow, Joel Gratz.

“One, it is a big driver of weather, in the wintertime in North America – and for Australia as well. The second reason is that it’s really the only thing that can give us some indication that that is predictable, three to six months in advance.”

Which resorts get the most snow during El Niño?

Ever heard forecasters talk about something sounding like “en-so”? They’re referring to the El Niño-Southern Oscillation (ENSO), which is a recurring pattern of changing water temperature in the eastern and central Pacific Ocean. When the ocean surface warms up in this region, it sparks an El Niño event – explained in better detail here by Gratz and the experts at Open Snow.

The gist of it is that the El Niño often sends the cold-weather Pacific jet stream lower through the USA and Canada. Southern states become cooler and wetter than average, while the northern areas become warmer and drier.

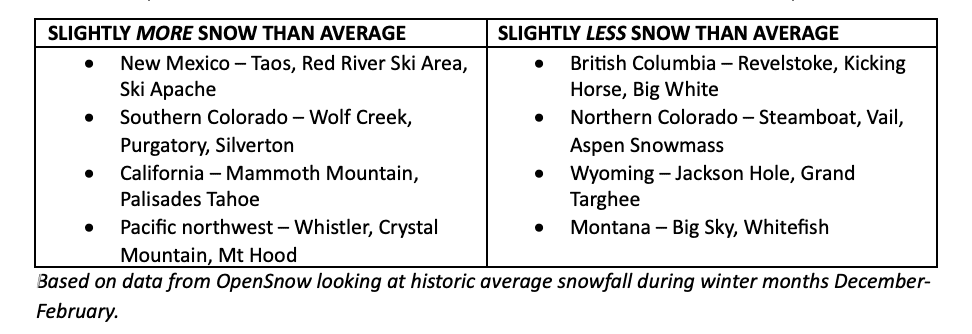

“A typical El Niño improves the chances for more precipitation, more snow along the southern part of the western United States, southern Colorado, New Mexico, Arizona, the southern half of California,” says Gratz.

“And sometimes El Niño makes it a little bit drier than average in the Northern Rockies – we’re talking about the main part of Colorado, main part of Utah, a lot of Wyoming, Idaho and Montana.”

But also, don’t bank on any of this

Be warned: booking a ski holiday based on long-term trends is a bit like leaving your umbrella at home on a sunny day. The sunshine later turns into torrential rain just when you’re due to commute home.

“The problem is that El Niño is not the only determinant of where it’s going to snow. I wish it were because we all have a lot more confidence. But it’s only one,” Gratz says.

“The best thing that we can do is go back over the last 50 years and find other seasons that had a moderately strong El Niño and see what happened. But unfortunately, it’s just not clear cut. No two El Niño seasons are the same.

“One interesting thing is leading up to this El Niño, there are already some anomalies. El Niño impacts hurricane systems in particular ways during summer, and this season hasn’t necessarily conformed to what a traditional El Niño season would look like for tropical cyclone and hurricane activity. Does that mean the snowfall also won’t conform?”

Want powder? You need to stay flexible

Gratz’ best advice for Australians who need to book flights and submit their annual leave in advance is to rent a car and keep a flexible itinerary.

Heading somewhere like northern Colorado makes it easy to move – to Utah (about six hours’ drive), north to Wyoming, or south to New Mexico, depending where the systems hit. Alternatively, base yourself at a known snow magnet for long enough, and you’ll likely get a storm.

“If you want to lock it in, you might try Tahoe, which is right on the border of a typical El Niño system. Or northern Utah, where generally there’s not much of a correlation with El Niño and La Niña. You may get a hair lower than average snowfall, but still Alta and Snowbird get more than almost anywhere else anyway,” Gratz says.

Looking ahead, how does El Niño affect Australian snow?

If you’re wondering why your August ski trip to the Australian slopes featured so many rocks, you can blame El Niño for that, too.

“On average, snow seasons during El Niño have a lower maximum snow depth than the all-seasons average, as well as a shorter snow season length. El Niño events are typically drier than average, meaning less natural snowfall,” says climatologist Caitlin Minney from the Bureau of Meteorology (BOM).

However, Minney adds that “several factors can influence the snow season, so it is hard to attribute what influenced the lack of snow this season”. Global warming is undoubtedly having impact.

“The long-term warming trend would also likely be a contributing factor in hastening snow melt, reducing peak snow depth and season length,” she says.